[ad_1]

Constructing fortified border fences was once an anomalous observe. In 2022, that is not the case. The state-driven coverage of fortifying nationwide border perimeters with a variety of military-inspired strategies – together with concrete partitions, electrified fences geared up with top-notched radars, and management towers – has develop into a very international phenomenon. This proliferation is illustrated with quantitative proof. Whereas within the early Nineties there have been twelve border fortified fences (Vallet, 2016), thirty years later, the quantity has sky-rocketed to round 80 (Vernon & Zimmermann, 2021), and the tendency is rising as new border partitions are being constructed and deliberate throughout the globe. For the reason that publication of Vernon and Zimmermann’s article, a number of new fortified fences have emerged in numerous borders, inter alia between Serbia-North Macedonia (N1 Belgrade, 2020), Dominican Republic-Haiti (BBC, 2021), and the Individuals’s Republic of China-Myanmar (Qi & Zhai, 2022).

This debunks the favored fantasy that the top of the Chilly Battle led to endof border partitions. The so-called ‘Anti-Fascist Safety Rampart’ (the official identify of the Berlin Wall, based on the GDR authorities) and different Iron Curtin fortified fences had been certainly torn down (Szábo, 2018), following the collapse of communist governments in Central and Jap Europe and break-up of the Soviet Union. The purpose, nonetheless, is that the tearing down of those fortified fences didn’t imply that each one border partitions had been gone, or certainly, that the observe of wall-building had magically disappeared from the face of the earth. In reality, the post-Chilly conflict interval has been buoyant for this observe.

The fortified borders in Ceuta and Melilla

That is the place Ceuta and Melilla, two Spanish maritime enclaves in North Africa of roughly 80,000 inhabitants every, enter the stage. Practically a decade in the past, I predicted that removed from being an remoted case, the border fortification practices in these enclaves might ‘doubtlessly develop into a development at different European borders’ (Castan Pinos, 2013: 53). Constructing on this argument, the current article claims that these two cities, which have been used as illustrative examples of ‘rebordering’ (Ferrer-Gallardo, 2008) and the ‘fortress Europe’ metaphor (Castan Pinos, 2009), might be thought of the pioneers (at the very least within the European context) of the post-Chilly conflict border fortification development.

The bodily obstacles surrounding all the land perimeters of Ceuta and Melilla had been initially erected within the mid-Nineties by the Spanish authorities. The timing is especially attention-grabbing, not least, as a result of that is the interval when many in Europe had been creating metanarratives primarily based on the parable of ‘borderless Europe’(Castan Pinos & Radil, 2020). There may be an extra chronological coincidence. The identical yr the Spanish authorities accredited the plan to construct the fortified fence in Ceuta (1993) the Clinton administration started implementing its anti-immigration technique, primarily based on fortifying the US-Mexico border by – amongst different devices – the erection of ‘a 10-foot-high metal fence’ within the El Paso and San Diego borderlands (Cornelius, 2005: 779).

Like within the US-Mexico border, the fortification of the border perimeters between the 2 Spanish cities and Morocco was primarily pushed by the intention of stopping the entry of irregular migrants. That is under no circumstances distinctive. As numerous authors have argued, the chief intention of fortified fences is (most often) to impede and deter the infiltration of undesirable people – specifically migrants (Hassner & Wittenberg, 2015; Schain, 2019). The so-called migration disaster within the enclaves might be illustrated with information: whereas in 1993, the Spanish safety forces had expelled a complete of eighteen migrants from each territories, two years later, in 1995, the variety of devolutions had impressively surged to fifteen,729 (Spanish Nationwide Police, 2008). Additional, in October of that yr, severe riots erupted in one of many enclaves, Ceuta, involving stranded migrants[1], safety forces and native residents (Lizarralde, 1995).

The incidents had been of nice concern for the Spanish authorities, which feared that the disaster in these ‘delicate’ territories might spiral uncontrolled. Right here, it is very important briefly clarify why these territories are thought of delicate by the Spanish authorities. Ceuta and Melilla are surrounded by Morocco, a state that claims sovereignty over each cities. It’s subsequently in Madrid’s greatest curiosity to minimise crises in these enclaves, as instability can doubtlessly translate right into a quagmire that may problem the territorial establishment, that’s, the Spanish sovereignty over the 2 cities (Castan Pinos, 2014b). Thus, whereas stopping migration is the important thing issue behind the border fortifications in Ceuta and Melilla, problématiques related to sovereignty and bilateral geopolitical rifts should even be thought of as subsidiary elements.

At any charge, per week after the incidents in Ceuta, on 18 October 1995, the Spanish Ministry of the Inside on the time, Juan Alberto Belloch made an announcement on the Spanish Congress which might have pivotal penalties. The minister introduced ‘concrete measures […] to sort out the true issues affecting Ceuta. First, we’ll seal off the border […]. From tomorrow on, we’ll proceed with the set up of a wire fence everywhere in the [border] perimeter’ (Spanish Congress, 1995: 9385). Whereas the fortification of the border had been initially deliberate in 1993, this declaration represented a turning level (Castan Pinos, 2014a), accelerating its implementation. Only a day later, members of the Spanish Legion started the development of a 3.5-meter barbed-wire fence in Ceuta. In Melilla, which had additionally skilled related crises, the development of the border fences started in 1996.

Did the fortification coverage work?

The substantial funding[2] to construct the border fortifications begs the crucial query of whether or not this pricey infrastructure has been efficient when it comes to stopping and deterring migration flows in Ceuta and Melilla. At first look, they haven’t. Hundreds of people are capable of irregularly enter the enclaves annually, empirically demonstrating that the border fences are removed from impenetrable. Additional, the fortifications have inspired different methods (e.g., coming into the enclaves by the ocean) and have confirmed to be significantly susceptible to ‘collective storms’. As detailed by Andersson, the governmental militarisation of the border has generated counterproductive results, such because the sophistication – and militarisation – of migrant’s methods aimed toward crossing the border fences (2016).

As an example, in early October 2005, almost a thousand folks had been capable of cross the fence by properly co-ordinated ‘collective storms’, with the tragic results of fourteen migrants killed and lots of injured (Amnesty Worldwide, 2006; European Parliament, 2006). On the one hand, this tragic incident consolidated the enclaves’ picture of notorious gates of ‘Fortress Europe’ (Castan Pinos, 2014a). On the opposite, it led to the strengthening of the border fences, which had been bolstered with concertina wire (eliminated in 2020) and elevated from 3.5m to 6m (Castan Pinos, 2009). The reinforcement didn’t stop additional incidents; within the interval 2012-2019, dozens of comparable ‘collective storms’, sometimes called avalanches by the Spanish press, occurred each in Ceuta and Melilla.

The small print supplied within the earlier paragraphs would appear to point that the fences have failed in undertaking their mission. Nonetheless, from the Spanish authorities’s large image perspective, the fences have been fairly profitable. How so, some readers might marvel? For one factor, because the border fences had been constructed, the enclaves are not what in Frontex jargon is known as a ‘major migratory route into the EU’ (see Frontex, 2021). In different phrases, the enclaves, in contrast to within the mid-Nineties, are not vital ‘entry factors’. This ‘success’ is illustrated by the truth that, in 2021, solely 5,4% of irregular entries to Spain occurred by Ceuta and Melilla (Spanish Ministry of Inside, 2022). Subsequently, whereas migrants proceed to cross into the enclaves, their quantity is sufficiently low for the safety forces to manage their flux, and most significantly, the Spanish authorities is ready to keep away from large-scale crises in ‘delicate’ territories. The truth that fences don’t clear up the roots of the issue and as an alternative generate incentives for brand spanking new migration routes is a good argument, however – sadly – it goes past the scope of this text.

Whereas they will be the most visible side of the combat in opposition to irregular migration, these fashionable border fortifications couldn’t be efficient with out an indispensable aspect; the collaboration from the Moroccan safety forces on the different facet of the border (Castan Pinos, 2014; Schain, 2019). Rabat’s collaboration shouldn’t be unintentional nor gratuitous because it receives appreciable EU funds to particularly shield the border. Morocco’s substantial and multifaceted contribution consists of the everlasting militarily patrolling of the border perimeter, the destruction of migrant’s camps (Castan Pinos, 2009; Andersson, 2016; Johnson & Jones, 2018) and its personal barbed-wire fence on its territory (Sampere, 2021).

Spain’s safety reliance on Morocco to guard the border perimeter inexorably empowers the latter, which might doubtlessly weaponise migration – by for example manufacturing a safety disaster on the border – for geopolitical functions (see The Economist, 2021).

Border Fortification in Ceuta and Melilla and past

An attention-grabbing side of fortified border fences is that the grounds for the justification of latest ones fairly often lie within the building of earlier related partitions by different actors. Thus, the Greek authorities justified the choice to erect a 5-metre-high fortified metal fence on its border with Turkey in 2011 utilizing the Ceuta and Melilla fences for example that prompted ‘constructive outcomes’ (Ekathimerini, 2011). In flip, stated metal fence on the Greek-Turkish border ‘impressed’ the Polish authorities for its newly constructed border fortification with Belarus (Reuters, 2021). In different phrases, previous border fences serve in a self-fulfilling style as fashions and precedents to legitimise the development of comparable new fences.

Ceuta and Melilla might be thought of because the pioneers of the brand new wave of post-Chilly conflict border fortification observe. A observe which is these days systemic. Whereas the President of the European Fee, Ursula von der Leyen, has constantly insisted that the EU wouldn’t finance ‘barbed wire and partitions’ on the borders (European Parliament, 2021), the inconvenient actuality is that the EU is roofed with border partitions. In keeping with a current report, there are, as of December 2021, 1800km of border partitions (the equal of 12 Berlin Partitions) in Europe, most of them separating EU member states from non-members (Rigby & Crisp, 2021). That is, to say the least, paradoxical given the truth that the EU has constantly used the narrative of borderless Europeto acquire legitimacy (Castan Pinos & Radil, 2020; Radil et al., 2021). Nonetheless, it isn’t simply ‘Fortress Europe’. The proliferation of border fortifications shouldn’t be solely a European phenomenon however a distinguished international development current in 4 totally different continents.

Lastly, it is very important notice that fortified border fences have implications that transcend their utilitarian use. These dispositifs of energy are a quintessential aspect of what has been termed the ‘international border regime’ (Radil et al., 2021) – a regime the place states throughout the globe use border fortification practices to ‘shield’ themselves from numerous threats but in addition to challenge energy. As argued above, the prominence of this instrument is self-reinforcing, as previous border fortresses function pretexts and inspirations for brand spanking new partitions and fences. Borrowing from O’Dowd, the sobering conclusion is that we stay in a ‘world of borders’ moderately than in a ‘borderless world’ (2010). Ceuta and Melilla are simply the tip of the iceberg.

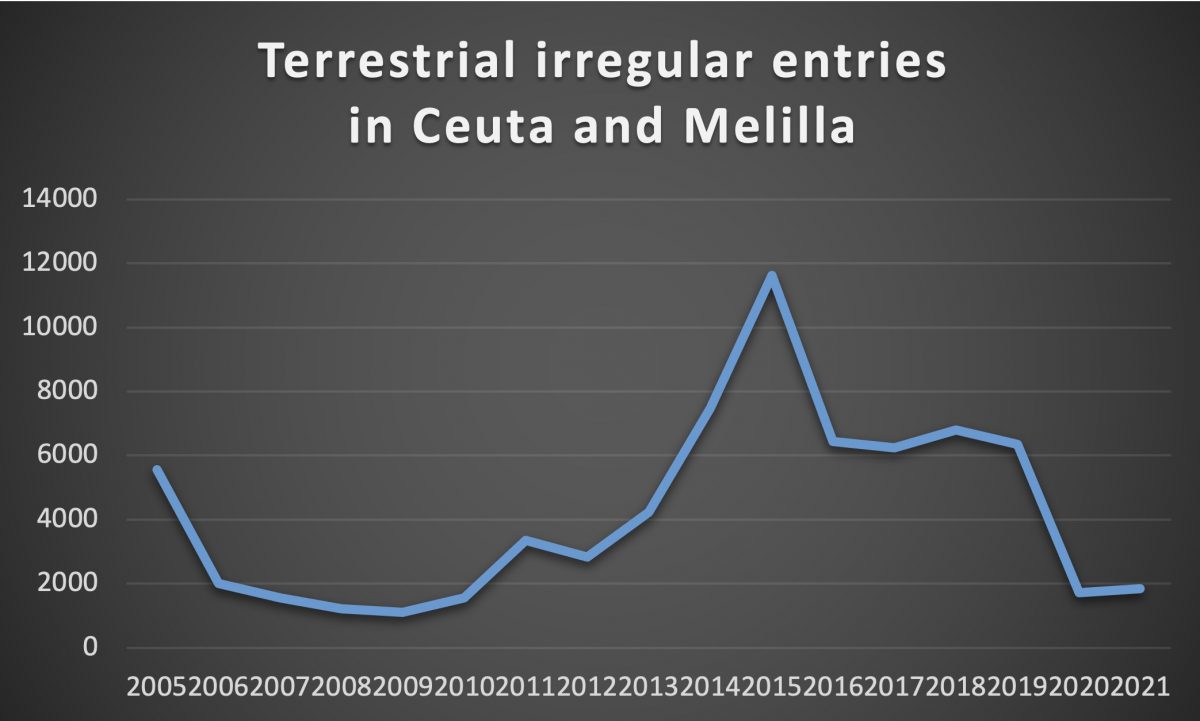

Determine

Determine 1: Irregular Land Entries in Ceuta and Melilla (2005–2021). Elaborated by writer primarily based on Spanish Ministry of Inside (2006–2022).

References

Amnesty Worldwide (2006). Spain and Morocco: Failure to guard the rights of migrants Ceuta and Melilla one yr on. Accessible at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/paperwork/EUR41/009/2006/en/

Andersson, R. (2016). Hardwiring the frontier? The politics of safety know-how in Europe’s ‘combat in opposition to unlawful migration’. Safety Dialogue, 47(1), 22-39.

BBC (2021, 28 February). ‘Dominican Republic declares plans for Haiti border fence’. Accessible at: https://www.bbc.com/information/world-latin-america-56227999

Castan Pinos, J. (2009) ‘Constructing Fortress Europe? Schengen and the Circumstances of Ceuta and Melilla’ Centre for Worldwide Border Analysis (CIBR)-WP 18/2009: 1-29.

Castan Pinos, J. (2013) ‘Assessing the importance of borders and territoriality in a globalized Europe’, Areas & Cohesion, 3(2): 47–68.

Castan Pinos, J. (2014a). La Fortaleza Europea: Schengen, Ceuta y Melilla. Ceuta: Instituto de Estudios Ceutíes.

Castan Pinos, J. (2014b). ‘The Spanish-Moroccan Relationship: Combining Bonne Entente with Territorial Disputes’. In Stokłosa, Okay., & Besier, G. (Eds.) European Border Areas in Comparability (pp. 110-126). Routledge.

Castan Pinos, J., & Radil, S. M. (2020). The Covid-19 pandemic has shattered the parable of a borderless Europe. LSE European Politics and Coverage (EUROPP) weblog.

Cornelius, W. A. (2005). Controlling ‘undesirable’immigration: Classes from the USA, 1993–2004. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Research, 31(4), 775-794.

Ekathimerini (2011, 24 Might). ‘Greece following Spanish mannequin for Evros fence’. Accessible at: https://www.ekathimerini.com/information/133700/greece-following-spanish-model-for-evros-fence/

El Confidencial (2021, 24 August). ‘El mantenimiento de las vallas y puestos fronterizos de Ceuta y Melilla costará 9,7 millones de euros en cuatro años’. Accessible at: https://www.elconfidencialdigital.com/articulo/seguridad/mantenimiento-vallas-puestos-fronterizos-ceuta-melilla-costara-97-millones-euros-4-anos/20210823194952270045.html

European Parliament (2006). ‘Report from the LIBE Committee Delegation on the Go to to Ceuta and Melilla’. Accessible at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/doc/LIBE-PV-2005-12-07-1_EN.pdf

European Parliament (2021). ‘Query for written reply to the Fee E-005077/2021’. Accessible at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/doc/E-9-2021-005077_EN.html

Ferrer-Gallardo, X. (2008). The Spanish–Moroccan border advanced: Processes of geopolitical, useful and symbolic rebordering. Political Geography, 27(3), 301-321.

Frontex (2021). ‘Danger Evaluation for 2021’. Accessible at: https://frontex.europa.eu/publications/?class=riskanalysis

Hassner, R. E., & Wittenberg, J. (2015). Limitations to entry: Who builds fortified boundaries and why?. Worldwide Safety, 40(1), 157-190.

Johnson, C., & Jones, R. (2018). The biopolitics and geopolitics of border enforcement in Melilla. Territory, Politics, Governance, 6(1), 61-80.

La Vanguardia (2014, 10 September). ‘El Gobierno ha invertido cerca de 72 millones en las vallas de Ceuta y Melilla desde 2005’. Accessible at: https://www.lavanguardia.com/sucesos/20140910/54414855442/interior-invierte-casi-72-millones-en-vallas-de-ceuta-y-melilla-desde-2005.html

Lizarralde, C. (1995, 12 October). ‘Un policía herido de bala y 150 inmigrantes ilegales detenidos en una batalla campal en Ceuta’.Accessible at: https://elpais.com/diario/1995/10/12/espana/813452417_850215.html

N1 Belgrade (2020, 18 August). Serbia builds wire fence on border with North Macedonia. Accessible at: https://rs.n1info.com/english/information/a630957-rfe-serbia-builds-wire-fence-on-border-with-north-macedonia/

O’Dowd, L. (2010). From a ‘borderless world ’to a ‘world of borders’: ‘bringing historical past again in’. Atmosphere and Planning D: Society and House, 28(6), 1031-1050.

Qi, L & Zhai, Okay. (2022). ’China Fortifies Its Borders With a ‘Southern Nice Wall,’ Citing Covid-19 ‘, Wall Road Journal. Accessible at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-fortifies-its-borders-with-a-southern-great-wall-citing-covid-19-11643814716

Radil, S. M., Castan Pinos, J., & Ptak, T. (2021). Borders resurgent: in the direction of a post-Covid-19 international border regime?. House and Polity, 25(1), 132-140.

Reuters (2021, 4 October). ‘Poland seeks to bolster border with new tech amid migrant inflow’ Accessible at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/poland-seeks-bolster-border-with-new-tech-amid-migrant-influx-2021-10-04/

Rigby, J. & Crisp, J. (2021). ‘Fortress Europe’, The Telegraph. Accessible at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/fortress-europe-borders-wall-fence-controls-eu-countries-migrants-crisis/

Sampere, A. (2021, 18 July). ‘Marruecos levanta una nueva valla con concertinas en la frontera de Ceuta’, El Mundo. Accessible at: https://www.elmundo.es/espana/2021/07/18/60f2f101e4d4d8130b8b4699.html

Schain, M. A. (2019). The border: Coverage and politics in Europe and the USA. Oxford College Press.

Spanish Congress (1995). ‘Plenary Session 175, 18 October 1995’. Accessible at: https://www.congreso.es/busqueda-de-publicaciones?p_p_id=publicaciones&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=regular&p_p_mode=view&_publicaciones_mode=mostrarTextoIntegro&_publicaciones_legislatura=V&_publicaciones_id_texto=(CDP199510180177.CODI.)

Spanish Ministry of Inside (2006-2022). ‘Informe Quincenal sobre Inmigración Irregular’. Accessible at: http://www.inside.gob.es/paperwork/10180/12745481/24_informe_quincenal_acumulado_01-01_al_31-12-2021.pdf/70629c47-8b67-4e03-9fe8-9e4067044c16

Spanish Ministry of Inside (2019). ‘Las obras de modernización y refuerzo de la valla fronteriza en Ceuta y Melilla comenzarán antes de que acabe noviembre’. Accessible at: http://www.inside.gob.es/prensa/noticias/-/asset_publisher/GHU8Ap6ztgsg/content material/id/11144953

Spanish Nationwide Police (2008). Memorias Anuales 1991-2007: Estadística de Extranjería y Documentación.

Szabó, É. E. (2018). Fence Partitions: From the Iron Curtain to the US and Hungarian Border Limitations and the Emergence of International Partitions. Assessment of Worldwide American Research, 11(1), 83-111.

The Economist (2021, Might 22). ‘King Muhammad of Morocco weaponises migration’. Accessible: https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2021/05/22/king-muhammad-of-morocco-weaponises-migration

Vallet, E. (2016). Borders, fences and partitions: State of insecurity?. Routledge.

Vernon, V., & Zimmermann, Okay. F. (2021). ‘Partitions and Fences: A Journey By means of Historical past and Economics’. In Kourtit, Okay. et al. (Eds.) The Financial Geography of Cross-Border Migration (pp. 33-54). Springer.

Footnotes

[1] Migrants demonstrated in Ceuta to demand their switch to mainland Spain. This example shouldn’t be distinctive, fairly often migrants and asylum seekers discover themselves stranded within the enclaves as they’re unable to pursue their intention to succeed in mainland Spain/Europe. Most often, the Spanish authorities refuses to switch them with a purpose to stop the so-called pull issue. Which means that the enclaves de facto develop into open-air prisons for irregular migrants.

[2] The Spanish authorities initially spent €62 million to construct each border fences (Castan Pinos, 2014a). This was adopted by a €72 million funding in fence reinforcements within the interval 2005-2013 (La Vanguardia, 2014). Moreover, in 2019, €17,9 million had been spent with the intention of heightening some ‘vital areas’ of the fences to 10m and of ‘modernising’ them technologically (Spanish Ministry of Inside, 2019). Lastly, the ministry of inside assigned €9,7 further tens of millions for ‘fence upkeep’ for the interval 2022-2026 (El Confidencial, 2021).

Additional Studying on E-Worldwide Relations

[ad_2]

Source link